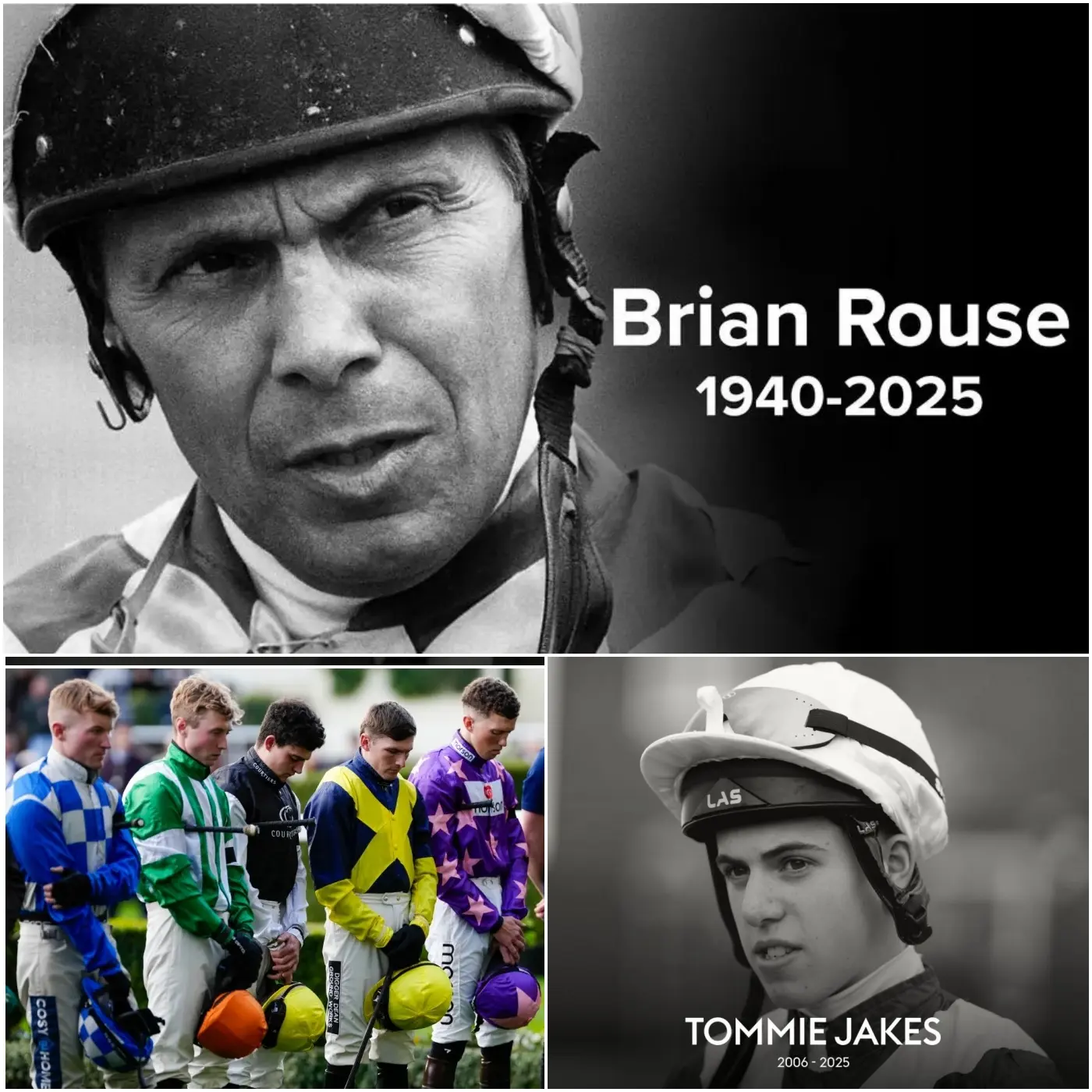

In the hallowed grounds of horse racing, where triumph and tragedy often gallop side by side, the sport’s community finds itself grappling with an unbearable double blow. Just as the echoes of grief over the untimely death of 19-year-old apprentice jockey Tommie Jakes began to fade, news emerged that has shattered hearts anew: the passing of Brian Rouse, the legendary British jockey who rode to glory in some of the 20th century’s most storied races. Rouse, aged 85, died on November 11, 2025, leaving behind a legacy etched in the annals of turf history and a void that feels as vast as the tracks he once conquered. For fans, trainers, and fellow riders still raw from mourning Jakes, this latest loss feels like a cruel twist of fate, a reminder that even the immortals of the saddle are not spared the final furlong.

Tommie Jakes’s death on October 30, 2025, struck like a thunderbolt, felling one of racing’s brightest young hopes before he could fully spread his wings. The Newmarket-based apprentice, who had burst onto the scene at just 16 with his first winner aboard Suzi’s Connoisseur at Lingfield in 2023, amassed an astonishing 59 victories from 519 rides over three short seasons. His final mount came the day before, a seventh-place finish on the 125-1 outsider Guarantee in a juvenile maiden at Nottingham Racecourse. Hours later, he was found dead at his family home near Newmarket, a place that should have been a sanctuary after the rigors of the weigh-in room. Police have confirmed the death is not suspicious, with a coroner’s inquest pending, but the “how” pales against the staggering “why”—a question that haunts everyone from his parents, Jeremy and Tonie, to the global racing fraternity.

Jakes was more than a statistic on the leaderboard; he was the embodiment of youthful promise laced with quiet grit. Trainers like George Boughey, for whom he rode with infectious enthusiasm, described him as “a hugely talented young rider with so much to look forward to, but an incredibly kind, popular, and hard-working young man.” Boughey’s yard, where Jakes had become an integral part, issued a statement that captured the collective ache: “We will miss him immensely.” Scottish trainer Linda Perratt, who gave him 169 rides and 17 winners—many on the unforgiving all-weather circuits—recalled him as a son-like figure, her voice breaking as she shared how he stayed with her family during northern campaigns. At Newcastle, where he notched 16 triumphs from 102 outings, Jakes was a local hero, his horsemanship earning nods from veterans who saw in him echoes of their own early fire.

The outpouring of tributes was swift and sorrowful. Jockeys donned black armbands at tracks across Britain, while minutes of silence rippled through Chelmsford, Southwell, and beyond. The British Horseracing Authority’s acting CEO, Brant Dunshea, spoke for many when he said, “We are devastated… He had the world at his feet.” Friends like 17-year-old Mason Paetel, choking back tears after a victory dedication, called him “my best friend,” underscoring the personal bonds that knit this tight-knit world. Even from afar, trainer Brian Meehan—preparing for the Breeders’ Cup in California—praised Jakes’s ride on Gascony at Epsom in August, a win in the famed Sangster silks that hinted at the classics he might one day claim. The Professional Jockeys Association and Injured Jockeys Fund urged those struggling to reach out, a poignant nod to the mental toll of a sport that demands perfection at perilous speeds.

Yet, as racecourses observed these rituals of respect, the racing calendar marched on, its relentless rhythm a bittersweet salve. Jakes’s parents, in their first public words since the loss, revealed a son brimming with plans: rides to chase, parties to host, a life unfolding like a well-bred colt’s stride. “He was planning for the future,” Tonie Jakes said, her words a dagger to the heart of a community that prides itself on nurturing the next generation. In an industry where apprentices like Jakes bridge the gap between boyhood dreams and professional peril, his absence is a stark warning. The weighing room, that fraternity of shared sweat and secrets, feels emptier, its laughter dimmed by the ghost of a kid who rode with joy.

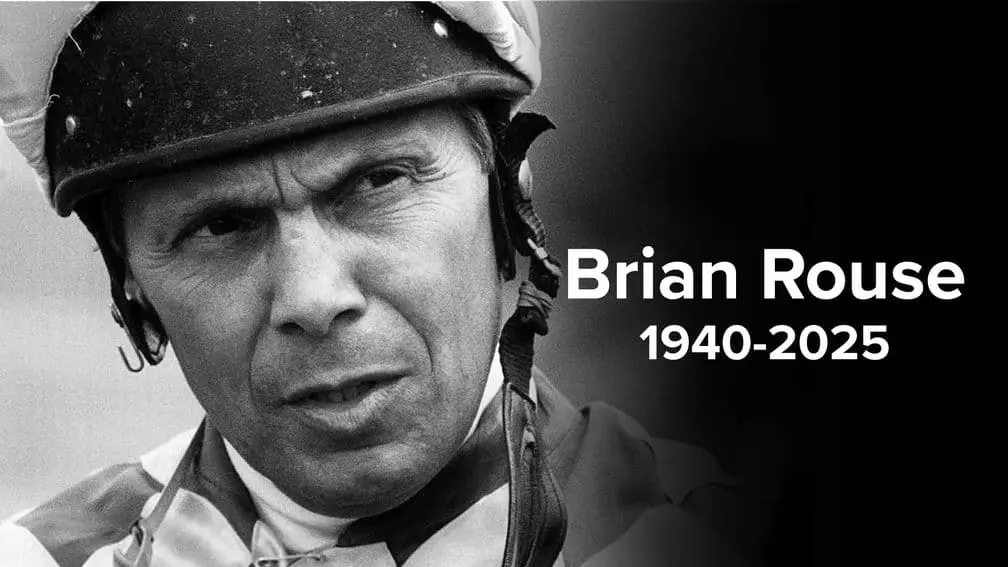

Into this fragile mourning stepped the news of Brian Rouse’s death, announced just weeks later on November 11, transforming fresh wounds into gaping ones. Born on April 5, 1940, in Fulham, London, Rouse was a journeyman turned icon, his career a tapestry of perseverance and improbable peaks. Apprenticed to Ted Smyth at Epsom, he claimed his debut victory on Gay Bird at Alexandra Park in 1957, but life took a detour: a 15-year hiatus as an electrician at Joe Lyons in Hammersmith, where the hum of wires replaced the thunder of hooves. Returning in 1972, he ignited a late-blooming blaze that would illuminate European racing.

Rouse’s triumphs were the stuff of legend. Aboard Quick As Lightning, he annexed the 1981 Irish 2,000 Guineas, a Classic that announced his arrival among the elite. That same year, on Stanerra, he added the Irish Oaks and, in a crowning jewel, the Japan Cup—becoming one of the first Europeans to conquer Tokyo’s turf. His seven Group wins in Germany during the 1980s and 1990s, including the Gran Premio d’Italia on Dashing Blade, cemented his status as a cross-Channel maestro. Over 38 Group successes in total, Rouse rode with a cool precision that belied his unconventional path, amassing respect from peers who marveled at his resilience. “From sparks to spurs,” one obituary quipped, capturing the electric arc of his journey.

At 85, Rouse’s death—reported by German racing outlet GaloppOnline as a quiet exit after a life richly lived—has prompted reflections on an era when jockeys like him defined the sport’s golden age. Tributes from Jockeypedia and Racing Post highlight his unassuming demeanor, a man who shunned spotlights yet lit up winner’s enclosures from Ascot to Milan. In interviews, he often credited luck and loyalty to horses, downplaying the skill that saw him navigate chaos with surgeon’s steadiness. His passing coincides with the Breeders’ Cup, a global stage he once graced indirectly through protégés, amplifying the sense of continuity—and rupture—in racing’s lineage.

For the sport’s faithful, these back-to-back losses compound a grief that defies easy consolation. Jakes represented tomorrow’s dawn, Rouse the storied dusk; together, they bookend a narrative of fragility amid exhilaration. Racecourses, those cathedrals of speed, now host not just cheers but choruses of remembrance—black armbands for the boy, bowed heads for the sage. As winter looms over Newmarket’s gallops, the question lingers: How does a community heal when its heart is trampled twice in a season? The answer, perhaps, lies in the rides yet to come, guided by the spirits of those who’ve crossed the finish line too soon. In their memory, the pain endures, but so does the passion that binds us to the rail.